https://www.oreilly.com/library/view/building-green-software/9781098150617/

I was initially disappointed with the lack of detail in this book, but by the end had changed my mind. It’s not a book about software performance tuning, but the much broader topic of how to minimise GHG emissions from real-world software systems. As such it needs to talk about business goals, economics, government policy, energy markets, operations and all the tradeoffs that span the gap between your systems’s theoretical compute complexity and how much GHG emissions it’s actually responsible for.

As such I would call this a guide book rather than a how-to.

The main things I took away were:

-

Embodied carbon - the emissions resulting from the creation and disposal of hardware - are a major source of GHG emissions that often get overlooked when discussing software emissions (it’s 85-95% for smartphones, it’s lower for servers, but still a lot)

-

High hardware utilisation is really really important, for two reasons:

- Higher utilisation from existing hardware means less new hardware needs to be manufactured which means you avoid all of that embodied carbon. Notably this applies to all hardware, even non-compute elements like network cabling.

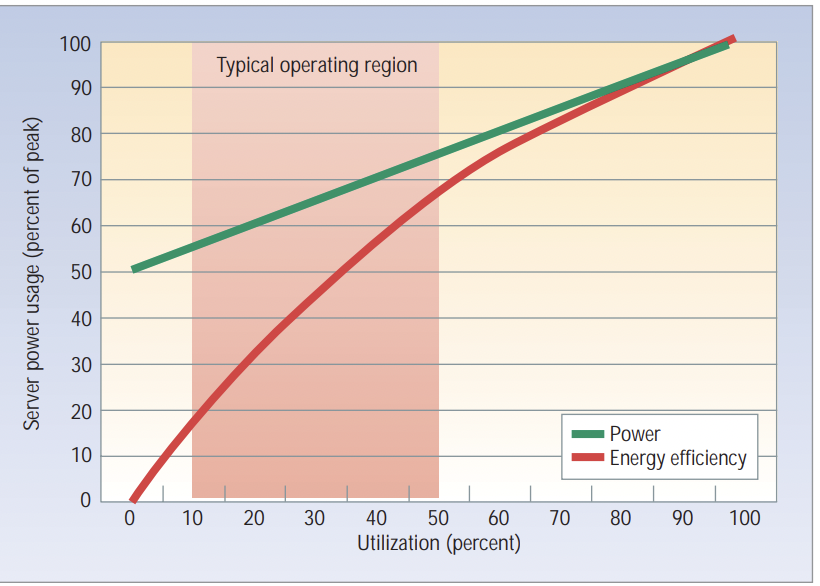

- An idle server consumes significant power, and power efficiency (compute per unit of power) is non-linear, with efficiency increasing as server utilisation goes up: ^7fda1e

(from https://static.googleusercontent.com/media/research.google.com/en//pubs/archive/33387.pdf. For illustrative purposes, actual numbers are out of date)

(from https://static.googleusercontent.com/media/research.google.com/en//pubs/archive/33387.pdf. For illustrative purposes, actual numbers are out of date)

-

The easiest and most scalable way of reducing software emissions is not tuning code efficiency, but running it more efficiently, ie: Operational Efficiency. Why? Optimised software comes with business costs. There is a tension between efficiency and developer productivity and software maintainability.

-

Operational efficiency: “achieving the same functional result for the same application or service, including performance and resilience, using fewer hardware resources”

- Run on a large cloud provider. They are incentivised to run your workloads as efficiently as possible and spend a lot of effort on cluster scheduling, multi-tenancy and efficient packing of workloads.

- Pick the right kind of scheduling/instance type for your workload. Eg: an large always-on instance will use way more resources than your time-insensitive batch job actually needs. Cloud providers will try and claw back some of these unused resources via things like oversubscription, but they can do more when you provide them with better signals.

- Pick lower-power instances if you can (various ARM offerings from the hyperscalers)

- Only run jobs when you need them.

-

Hardware needs to be provisioned for workload peaks. The wrong way to do this is to provision for the sum of the peaks and call it a day, ie: add up the peak requirements for all workloads regardless of where or when they run. The right way is to provision for the peak of the sums and minimise these peaks:

- Make workloads spatially and temporally flexible to take advantage of low utilisation in different places/at different times.

- Automatically scale their requirements based on recent history of workload size. This minimises the size of peaks (we’re not relying on some static conservative guess) and reduces their width (we don’t hold onto resources longer than they are needed).

-

FinOps and GreenOps are natural allies.

I was happy to see https://blog.google/outreach-initiatives/sustainability/carbon-aware-computing-location/ get a shout-out as an example of carbon-aware computing (spatial and temporal workload shifting to minimise GHG emissions). I’ve done some work to optimise the pipelines behind this as part of $dayjob and it’s nice to see the recognition, but i can say that the ability to do this kind of shifting goes down as fleets are run at higher utilisation and specialised ML hardware makes workloads more constrained. Which reminds me, I should write up some notes on the original carbon-aware computing paper

Lastly, there was of course a chapter on AI and LLMs. On the one had I don’t think the authors could have written a this book without addressing the elephant in the room, but on the other, the whole area is moving so quickly and seems so immune to rational economics that there’s not much useful they could say. Maybe in a few years when things have settled down.

Notes

Chapter 1 - Intro

- Embodied carbon (manufacture and disposal, scope 3) in hardware used is often the dominant source of emissions for software. 2019 Apple lifetime emissions analysis of iPhone showed 85% for embodied carbon

- The other source of major impact is writing software that helps solve real world emissions problems.

- Tuning software to use less power/carbon for most software (unless at a very large scale) is not where the big wins are.

- It’s important to run servers at high utilisation (~80%) for maximum efficiency because

- There is a non-zero power draw for an idle server, ie: a constant overhead that has to be paid per server, aka “static power draw”

- Compute/power efficiency is higher at higher utilisation (though I imagine this is better for a smaller number of workloads and worse for a larger number of workloads that may fight over resources and cause cache invalidation/context switching/interrupts etc).

from https://static.googleusercontent.com/media/research.google.com/en//pubs/archive/33387.pdf is illustrative (but actual numbers are out of date)

- Also

from Power Modeling for Effective Datacenter Planning and Compute Management

- Cloud providers are incentivised to run at high utilisation and spend a lot of effort on multi-tenancy and efficient packing of workloads. BUT I can’t find compelling numbers and the https://sustainability.aboutamazon.com/products-services/aws-cloud link in the book doesn’t seem to have them either.

- So anything that makes bin packing easier is good for lower emissions: smaller workloads relative to machine size, delayable workloads, scalable workloads

Chapter 2 - Building Blocks

- Embodied carbon means we should strive to 1) extend device lifetimes, 2) maximise devise utilisation. Both because they result in fewer devices needing to be manufactured.

- Power efficiency curve is another reason to maximise utilisation.

- PUE (power usage effectiveness): ratio of DC power usage to power used for “real work”, ie the work that isn’t cooling and other overheads. Modern hyperscalers have a PUE of < 1.2

Chapter 3 - Code Efficiency

- Main takeaway: the easiest and most scalable way of reducing software emissions is not tuning code efficiency, but running it more efficiencly, ie: Operational Efficiency discussed in the next chapter.

- Why is tuning code for efficiency often not as effective?

- Business cost: takes a lot of up front dev time and adds overhead to maintainability and any future integrations with other services. There is a tension between efficiency and developer productivity.

- So if we can somehow align developer productivity with GHG efficiency we have a much better chance of success. This points towards a focus on efficient libraries and platforms and tooling.

- Unless your software is running at a very large scale, the power/emission savings may not be significant. Note that this isn’t an argument against software tuning for performance reasons. But you’re likely doing that already if it’s a business requirement.

- More efficient code only (or mostly) helps if it results in fewer servers or existing servers running at lower power. Because of the power efficiency curve above, the “fewer servers” outcome is the much better one.

- Think multi-tenant environments with autoscaling and placement of task. Together these allow us to only provision of the peak of sums (not sum of peaks) and to minimise the duration of peaks. All without needing extra work from devs.

- Downside to multi-tenancy is the per-task overhead.

- Upside to multi-tenancy is that there is now a single system (the multi-tenancy) platform that can be optimised to provide efficiency savings at scale.

- No code examples for efficient code because that’s context dependent - fair.

- If you need to improve performance, start with profiling to identify bottlenecks.

- But making architectural choices are a way to build for efficiency:

- Pick a platform with features (eg: multi-tenancy, autoscaling, large scale) that support green computing and check that they are committed to future improvements.

- Avoid too many layers to reduce duplicate work, eg: encoding/decoding messages multiple times while crossing layers and/or microservices.

- Replace inefficient services and libraries with better alternatives. Profiling can help highlight these opportunities.

- Minimise unnecessary features, work and data storage.

- Offload work to client devices where possible. Those devices already exist so offloading work there should not result in more devices being manufactured, but can result in fewer servers.

Chapter 4 - Operational Efficiency

- “Operational Efficiency is about achieving the same functional result for the same application or service, including performance and resilience, using fewer hardware resources.”

- BUT efficiency can increase complexity and reduce resilience if you do not put the work in to mitigate.

- Apart from being a route to better efficiency without sacrificing developer velocity, it saves money for DC operators/cloud providers which means the incentives are aligned.

- As described in chapter 3, operational efficiency is likely less effective for individual pieces of software than code efficiency, but scales much much better and requires less work per unit of saving.

- Keys to better machine utilisation

- Rightsizing machines to workloads. But this is impractical.

- Autoscaling workloads. This allows lower average resource usage, shorter usage peaks and ultimately fewer servers.

- Cluster scheduling for better bin-packing (I was kind of assuming this one)

- Time-shifting workloads (or workload peaks). This allows higher utilisation of servers during lulls. The risk is that there isn’t enough slack during lulls to complete this lower-priority work.

- Infrastructure as code (IaC), eg: gitops - allows automation of more efficient deployments

- “LightSwitchOps”: turn off jobs/tasks when they are not being used. This can also expose hidden dependencies and issues with restarting long running jobs.

- Where you run is key to carbon intensity.

Chapter 5 - Carbon Awareness

- Doing more in your software when electricity is clean, and less when it is dirty: “carbon aware computing”

- Google’s efforts: https://blog.google/outreach-initiatives/sustainability/carbon-aware-computing-location/

- “we plan to completely decarbonize our electricity use for every hour of every day” by 2030

- shift moveable compute tasks between different data centers, based on regional hourly carbon-free energy availability. This is in addition to time-shifting.

- IME this has become harder with higher utilisation and location-specific hardware (ML chips) that some jobs must use

- “Our carbon-intelligent platform uses day-ahead predictions of how heavily a given grid will be relying on carbon-intensive energy in order to shift computing across the globe”

- Current per-grid carbon intensities: https://cloud.google.com/sustainability/region-carbon

- There are three kinds of demand shifting:

- spatial: this is harder because it requires geographical diversity, moving/duplication of data, data locality restrictions (including legal). But better if you can’t wait.

- temporal: easier since you’re running in the same place, but at a different time. But you do have to wait.

- demand shaping: really just a continuous version of temporal shifting. Instead of a binary choice of when to run/not run, do less work when electricity is dirty, and more it’s clean. In the limit this becomes on/off temporal shifting.

- Idea: CDNs tuned to update caches when electricity is greenest. What would the impact be though?

- A description of Google’s Carbon Aware Computing

- https://blog.google/outreach-initiatives/sustainability/carbon-aware-computing-location/

- Get per-hour per-grid carbon intensity forecasts from electricitymaps one day ahead.

- Google creates per-DC power usage forecasts and joins them with the carbon intensity data.

- These two data sets allow time and spatial shifting for batch workloads.

Chapter 6 - Hardware Efficiency

- Embodied carbon is 85%-95% if emissions for smartphones

- Embodied carbon datasets at https://sci-guide.greensoftware.foundation/M/Datasets

- How to minimise hardware emboddied carbon via software?

- Maximise hardware utilisation to minimise hardware required

- Increase the lifetime of hardware by not making it obsolete via new software

- Arm CPUs are much lower power (~60% savings) than x86: AWS Graviton, GCS and Azure using Ampere Altra processors , Google Axion Processors

Chapter 7 - Networking

- Networking has a history of load shifting and balancing in response to availability of bandwidth, so in a sense is ahead of compute and storage when it comes to adaptive resource usage.

- Network hardware (routers, cables, fiber, switches etc) is subject to the same emboddied carbon cost as already discussed and as such we have the same incentives to maximise utilisation/minimise new hardware to reduce emissions.

- In theory could add a carbon cost to BGP decisions, but it’s unclear what the outcome would be even assuming there was appetite to do it. BGP is complex, critical, and per Jon Berger “More of the networking behaviour of the internet is emergent than we like to think. Changing as fundamental a component as BGP will be easy or safe.”

- Conversely, poor software architecture is often the cause of inefficient network usage and that is easier and safer to fix.

- CDNs can help by

- time-shifting backbone transfers to increase utilisation of that part of the network

- reduce long haul traffic by keeping copies close to users

Chapter 8 - Greener Machine Learning, AI, and LLMs

- IMO this area is changing too fast and is too complex for a single chapter in this book to offer much.

Chapter 9 - Measurement

- To restate, the three things to consider when it comes to greener software

- energy utilisation

- carbon intensity of energy supply (typically the local grid)

- embodied carbon in hardware

- Proxies for carbon emissions that might be easier to measure

- energy usage

- cost

- hardware requirements

- ==Green Software Foundation’s Software Carbon Intensity Specification (SCI)

- per

- is energy consumed by software,

- is the carbon intensity: carbon emitted per kWh of energy, . Note that only allows for location-based intensity, not market-based (ie: no accounting for offsets, PPAs, RECs etc.)

- is the carbon emitted through the hardware that the hardware is running on. So the total embodied carbon multiplied by the fraction of the hardware’s expected lifetime that we are calculating over.

- is the functional unit of your software. Eg: per user/device/query==

- ISO 14064-{1,2,3}: supports market-based reduction techniques

Chapter 10 - Monitoring

- Apparently the Google SRE book recommends this minimal set of metric classes for monitoring

- Latency

- Traffic (QPS)

- Errors

- Saturation (CPU and memory utilisation)

Chapter 11 - Co-Benefits

- FinOps (saving operational costs) and GreenOps are natural allies

Chapter 12 - The Green Software Maturity Matrix

- https://maturity-matrix.greensoftware.foundation/gsmm/

- https://github.com/Green-Software-Foundation/green-software-maturity-matrix

Chapter 13 - Where Do We Go from Here?

- Things you can do now get major GHG savings

- Switch off jobs/servers that aren’t being used.

- One-off rightsizing of servers.

- Turn off test systems when not being used (evenings and weekends)

- Move stuff to the cloud

- For stuff in the cloud, review instance types, can you move to spot or burst instances, what about autoscaling? Can you move to ARM instances?

- Things that might take longer

- Use a cloud/hosting provider with real GHG reduction commitments

- Use machines on low CO2 grids

- Choose a software architecture that allows spatial and temporal load shifting

- Set high bars for machine utilisation. “The best way to both cut emissions and embodied carbon is to use fewer servers.”

- Don’t build features and don’t retain data before it’s needed.

- Make sure your software is never the thing that causes hardware obsolescence.

- Do basic performance analysis regularly to find and fix bottlenecks.

- If your code has to run all the time, make it efficient.