https://www.computer.org/csdl/magazine/mi/5555/01/11097303/28IR6YdAq9W (with a somewhat extended version here that goes deeper into the methodology)

Abstract: Specialized hardware accelerators aid the rapid advancement of artificial intelligence (AI), and their efficiency impacts AI’s environmental sustainability. This study presents the first publication of a comprehensive AI accelerator life-cycle assessment (LCA) of greenhouse gas emissions, including the first publication of manufacturing emissions of an AI accelerator. Our analysis of five Tensor Processing Units (TPUs) encompasses all stages of the hardware lifespan—from material extraction and manufacturing, to energy consumption during training and serving of AI models. Using first-party data, it offers the most comprehensive evaluation of AI hardware’s environmental impact. We introduce a new metric, compute carbon intensity (CCI), that will help evaluate AI hardware sustainability and estimate the carbon footprint of training and inference. We show that CCI improves 3x from TPU v4i to TPU v6e. Moreover, while this paper’s focus is on hardware, software advancements leverage and amplify these gains.

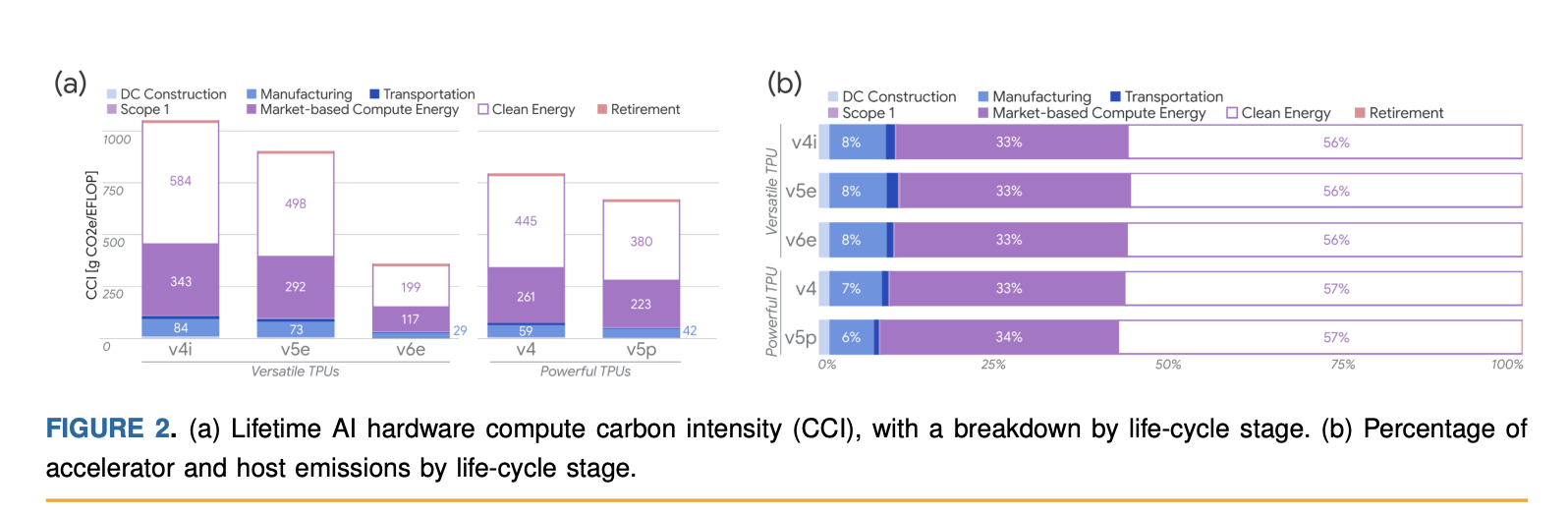

The main point: Google’s AI hardware has gotten 3x more emissions-efficient over the last four years, where emissions-efficient refers to CO2-equivalent emissions per floating-point-operation (FLOP).

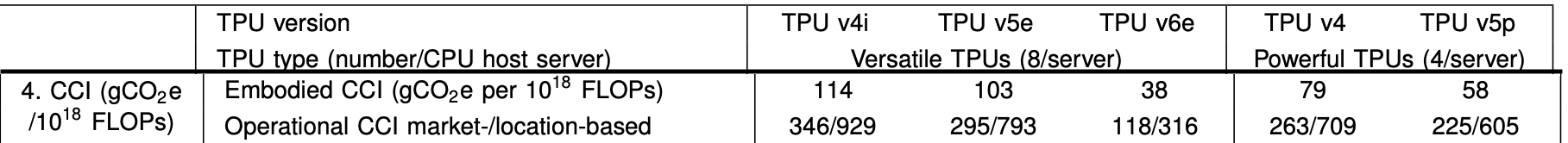

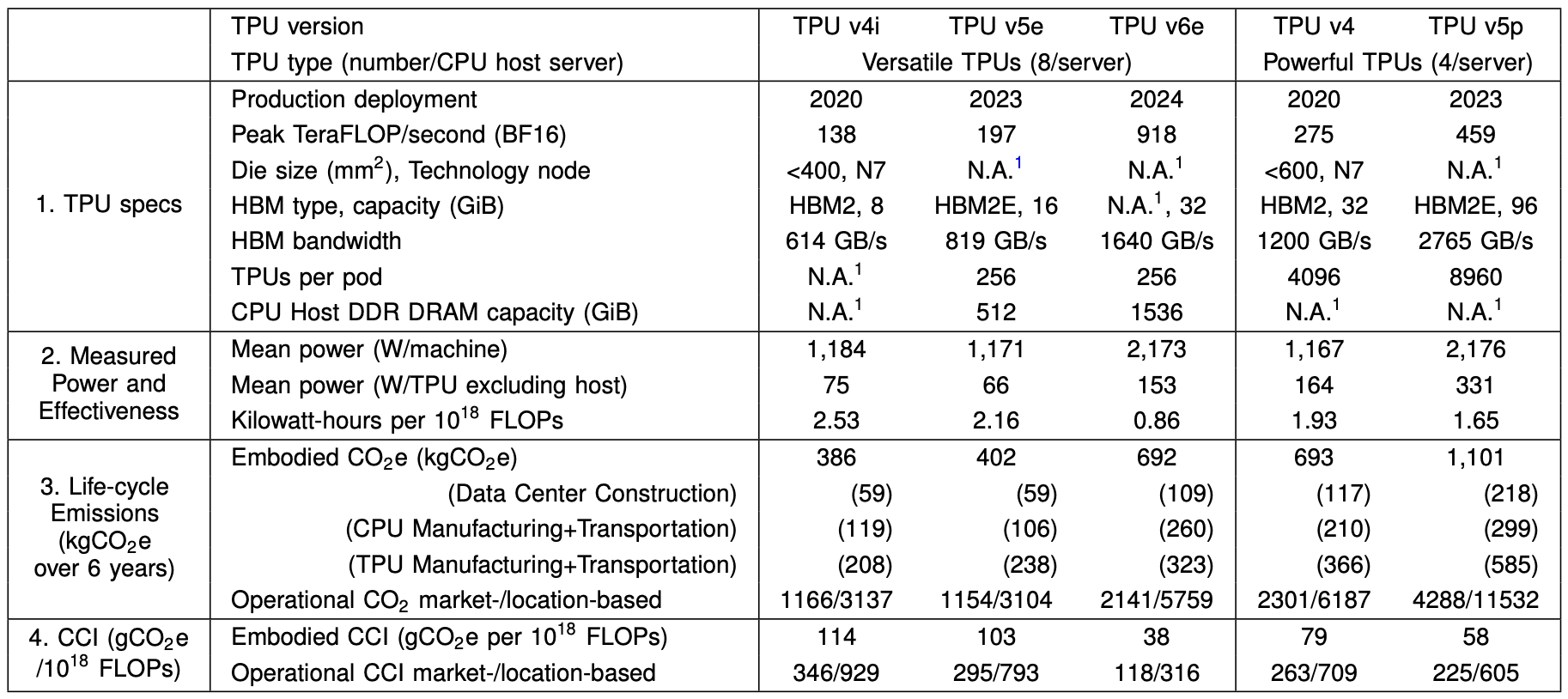

What’s going on in this table?

First, TPUs are broken down by type and generation. The Versatile type being good for training and inference while the powerful type is better for just training.

The authors define compute carbon intensity (CCI) as , or in words: grammes of CO2-equivalent emissions per exaFLOP (floating-point-operation). The paper later proposes using this a standard metric for future LCAs.

I’ll note that this seems like a specific implementation of SCI from the Green Software Foundation.

What about “market/location-based”? These are two different methods of accounting for electricity generation emissions factors (aka: carbon-intensity, CO2-equivalent emissions per unit of power), and I was happy to see them both included:

- location-based: You use the annual average electricity emissions factor of the local grid. This isn’t perfect, ideally we’d all use hourly-matching.

- market-based: You get to use the emissions factors from your Carbon Free Energy (CFE) procurements which could be very far away from the generation that you’re actually consuming (eg: all of the USA+Canada are considered in the same location). This is a controversial accounting method, and it’s certainly easy to see how it might not lead to actual emissions reductions.

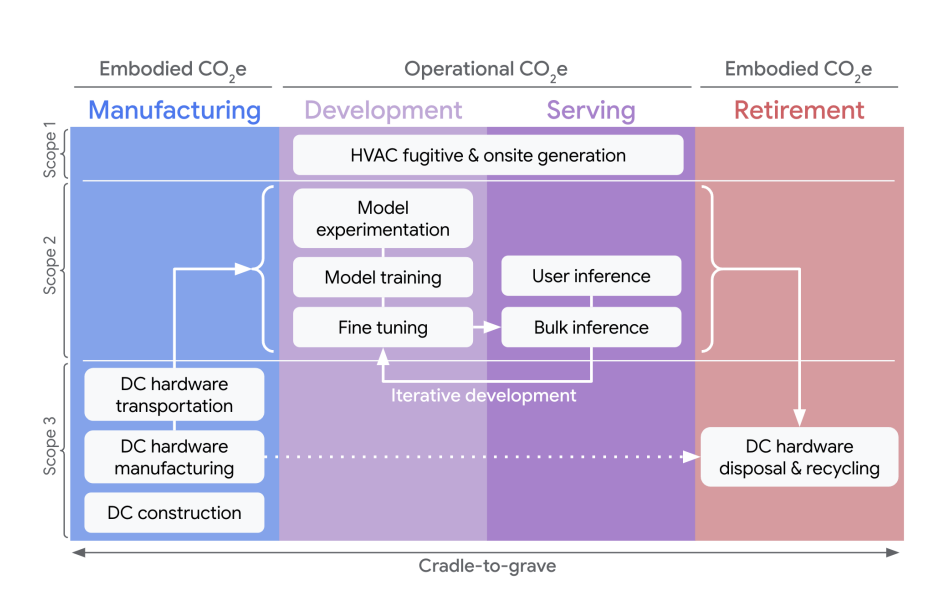

As we can see from the nice diagram at the top, embodied CCI accounts for DC construction, hardware construction, disposal and recycling, while operational CCI includes power to run the hardware as well as DC cooling. Operational emissions dominate, and “ignoring CFE procurement, embodied emissions are roughly ∼10% and operational emissions are ∼90% of an AI system’s lifetime emissions”.

One last thing that caught my attention was from the methodology: newer chip generations tend to see higher utilisation, and power-efficiency goes up with utilisation (see here). So in order to avoid modelling artificially higher efficiency for newer generations, the authors performed Propensity Score Weighting (see appendix F in the extended paper) to normalise utilisation across generations. For example, if most v4 machines run at low utilisation, then a v4 machine running at high utilisation gets a high weight applied to its utilisation value. This isolates hardware improvements from the utilisation differences.

If I have one quibble with this paper it’s that it probably underestimates the embodied CCI for a combination of two reasons:

- Utilisation of a specific generation of hardware seems likely to go down over time as newer hardware comes along. In fact this is the stated reason for implementing propensity weighting.

- Hardware may end up with less than the expected six year lifespan due to the rapid pace of change in all things AI.

Both of these will have the effect of reducing the total FLOPs performed by a chip in its lifetime which would raise the embodied CCI. With that said, we’ve already noted that operational CCI is much larger than embodied CCI so maybe it’s not that important.

Notes

- very nice the way this lays out scopes vertically and lifecycle stages horizontally.

- DC construction: DCs live much longer than hardware so one DC serves multiple generations

- Tensor Processing Units (TPUs) are Google’s AI-focused application-specific integrated circuits (ASICs)

- Does an LCA across multiple chip generations to study the trajectory of energy and carbon efficiencies.

- versatile good training and inference, powerful for training

- Methodology

- Paper targets AI accelerators and the attached host computer. So one TPU tray+ one compute tray. Network and storage equipment not included. DC cooling included in operational emissions.

- Appendix in the archivex paper is a tutorial on how to perform this kind of LCA.

- Uses a lifespan of six years.

- Two approaches to getting electricity emissions factors (ie: carbon intensity), 1) location-based (LB), so use the carbon intensity of the local grid, 2) market-based (MB), where you get to use the emissions factor of their Carbon Free Energy (CFE) procurement.

- Apparently scope 2 standards allow doing the latter on an annual basis within very loose geographical boundaries (eg: all of US and Canada considered fungible) which seems very sketchy

- MB emission factor = LB emission factor − Impact of procured CFE

- For 2023, Google’s LB emission factor was 366gCO2e/kWh and the reduction impact of its procured CFE was equivalent to 231 gCO2e/kWh, so the net MB emission factor was 135 gCO2e/kWh.

- This paper calculates for LB and MB (good, there are some very big differences in the results)

- CCI: A NOVEL EMISSIONS PERFORMANCE METRIC

- CCI: CO2e per utilised floating-point operation (FLOP), or CO2e/FLOP. The denominator of CCI is a fixed amount of computation, not a rate. Isn’t this the same as SCI](https://sci-guide.greensoftware.foundation/#:~:text=of%20that%20component.-,SCI%20Calculation,-SCI%20%3D%20(E)?

- From table above can see that embodied CCI is significant, but also significantly less than operational CCI for flops (ExaFLOP)

- Operational CCI

- FLOP count collected per chip every 5m

- Higher utilization leads to better CCI, as idle machines consume power but don’t compute (idle power and power curve). So adjust for fraction of an interval a chip is in use (aka: duty cycle) with propensity score weighting. This allows a balanced comparison of machines at similar duty-cycle utilization levels.

- Downside of using FLOPS is that we anchor to current state of algorithms, ie: algo improvements would not show up as CCI improvements.

- measured operational CCI varies from 2 to 4 times higher than spec sheet operational CCI across the five TPUs.

- Results

- Some speculation about a world where 90% of operational and manufacturing energy was 90% carbon free. I’m not sure I see the point of this in this paper. Feels like the author wants to write a separate paper about carbon accounting under future higher CFE conditions.

- Ignoring CFE procurement, embodied emissions are roughly ∼10% and operational emissions are ∼90% of an AI system’s lifetime emissions. DC operation ~5%. So operational efficiency or more CFE for running systems is where we should be focusing for now.

- Newer TPUs and more memory increase embodied emissions in newer generations — representing more than half of all embodied emissions with memory alone more than a third—yet CCI from manufacturing still declines each generation, suggesting performance gains via more efficient hardware design outweigh increases in manufacturing emissions.

- CCI as measured across Google’s fleet declines with each TPU generation, delivering a 3x improvement in CCI from TPU v4i to TPU v6e (Trillium).