https://www.nature.com/articles/s41545-021-00101-w

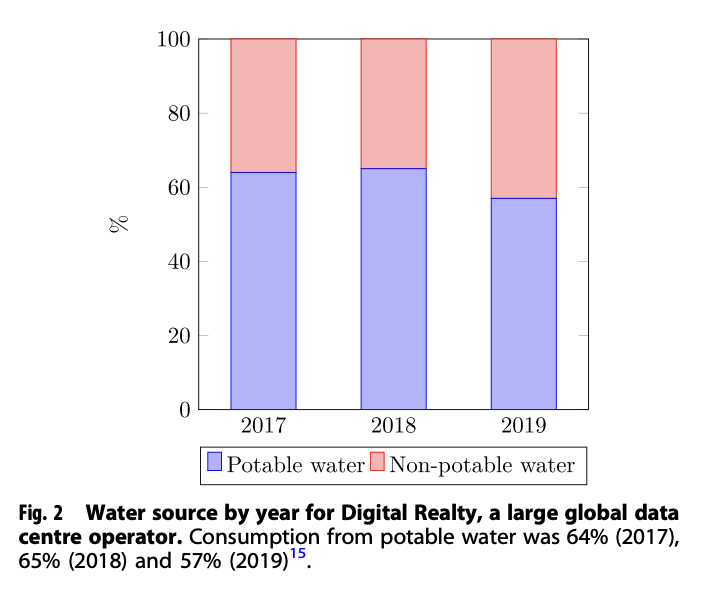

Abstract: The information communication technology sector will experience huge growth over the coming years, with 29.3 billion devices expected online by 2030, up from 18.4 billion in 2018. To reliably support the online services used by these billions of users, data centres have been built around the world to provide the millions of servers they contain with access to power, cooling and internet connectivity. Whilst the energy consumption of these facilities regularly receives mainstream and academic coverage, analysis of their water consumption is scarce. Data centres consume water directly for cooling, in some cases 57% sourced from potable water, and indirectly through the water requirements of non-renewable electricity generation. Although in the USA, data centre water consumption (1.7 billion litres/day) is small compared to total water consumption (1218 billion litres/day), there are issues of transparency with less than a third of data centre operators measuring water consumption. This paper examines the water consumption of data centres, the measurement of that consumption, highlights the lack of data available to assess water efficiency, and discusses and where the industry is going in attempts to reduce future consumption.

This paper is a bit old, but I wanted to something that was introductory before diving into newer stuff and all the extra complexity around AI resource consumption.

How much water is a lot?

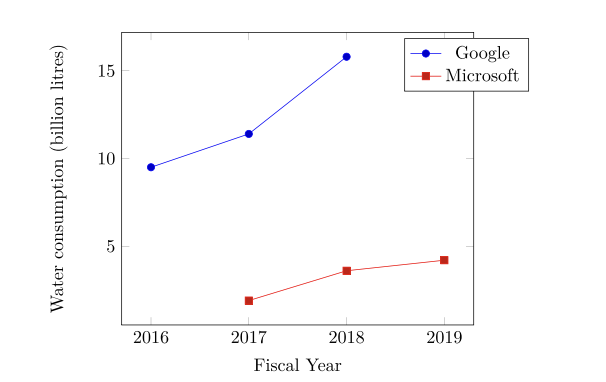

Here is the annual water consumption for Google and Microsoft (the only two hyperscalers publishing data at the time) from 2016 to 2018/2019:

15 billion litres sounds like a lot! And it’s actually worse than that. The most recent figures for Google, are ~30.6 billion litres in 2024, while Microsoft consumed ~12.9 billion litres in 2023. I think we can safely assume those numbers have increased again for 2024/2025.

BUT, it turns out that the entire USA consumes ~1217 billion litres per day, or ~444 trillion litres annualised, roughly broken down as:

- 183 trillion: thermoelectric power

- 162 trillion: irrigation

- 54 trillion: to supply 87% of the US population with potable water

Those billions of litres for datacentres sure look like a rounding error compared to the trillions used across the US. But similar to discussions about datacentre energy consumption and emissions, it’s important to realise that this consumption is not spread evenly across the country. It is concentrated in a relatively small number of locations and it’s perfectly reasonable to be worried about the stress a giant new datacentre may put on the resources of a local community.

What does it mean to “use” water?

There are at least three dimensions of usage to consider.

1. Result of usage

Water can be withdrawn, where it is taken from a source and later returned to that source, or consumed, in which case it is lost (typically through evaporation.)

Consumption is clearly more impactful for the locality, though withdrawal may also have negative effects depending on the state (temperature, chemical composition) and exact location of the water when returned.

2. Method of usage

Datacentres can use water indirectly through the electricity they consume (eg: steam turbines in a coal plant), or directly for cooling.

Electricity generation

Thermal generation uses water for cooling and running steam turbines and usage can vary by orders of magnitude. Eg: a dry air cooling system for a natural gas combined cycle generator consumes and withdraws 0.00–0.02 L/kWh, whereas a wet cooling system for a coal steam turbine consumes 0.53 L/kWh and withdraws 132.5 L/kWh!

Hydro has quite a high average consumption rate of 16.8 L/kWh due to evaporation in reservoirs and released water not being returned to reservoirs.

Solar and wind do not use water during generation, but do during manufacturing (but then so does everything).

Cooling

There are few different cooling methods that consume water:

- Cooling towers where external air travels across a wet media so the water evaporates. Fans expel the hot, wet air and the cooled water is recirculated into chillers in the DC.

- Adiabatic cooling where water is sprayed directly into the air flow, or onto a heat exchange surface and cools the air entering the DC.

In cooler regions it’s also possible to do free air cooling where cold air is drawn from the external environment. Though I imagine you still need to plan and provision for times when the external temperature is too high for cooling.

3. Type of water used

Is the water potable or non-potable. The more potable water consumed, the less there is for the local population and agriculture.

There are examples of non-potable water cooling like using sea water cooling for Google’s Finland DCs, or recycling grey water. But any filtering or treatment required to use this water adds to the carbon footprint of the DC.

After all this, we are left with two metrics for water usage effectiveness:

The second is preferable since it includes direct and indirect water usage, but some operators only publish the first.

Notes

- For 2023/2024:

- Google from https://www.gstatic.com/gumdrop/sustainability/google-2025-environmental-report.pdf, ~30.6 billion litres in 2024

- Microsoft from https://www.statista.com/statistics/1500284/microsoft-water-withdrawals-worldwide/ (2024 data not available), ~12.9 billion litres

- Compared to estimate of 1217 billion litres/day for all of USA (from https://www.usgs.gov/mission-areas/water-resources/science/total-water-use?qt-science_center_objects=0#qt-science_center_objects)

- thermoelectric power used 503 billion litres

- irrigation used 446 billion litres

- 147 billion litres per day went to supply 87% of the US population with potable water

- DCs consume water across two categories

- indirectly through electricity generation (traditionally thermoelectric power)

- withdrawal: taken from a source and later returned to the source.

- consumption: water lost, usually through evaporation (eg: cooling or steam turbines)

- directly through cooling.

- DCs often draw potable water, eg:

- US average water water intensity for electricity generation in 2015 was 2.18 L/kWh. Varies a lot across generation and cooling types.

- Hydro loses a lot of water due to reservoir evaporation. The US national average water consumption for hydropower is 16.8 L/kWh compared to 1.25 L/ kWh for thermoelectricity17

- Solar and wind do not use water during generation, but do during manufacturing.

- Cooling methods:

- chillers to cool water to then cool the air. Sometimes heatpumps, and sometimes cooling towers where external air travels across a wet media so the water evaporates. Fans expel the hot, wet air and the cooled water is recirculated

- adiabatic economisers where water sprayed directly into the air flow, or onto a heat exchange surface, cools the air entering the data centre

- Both cooling towers and adiabatic economisers result in evaporative loss. 1 MW data centre using one of these types of traditional cooling can use around 25.5 million litres of water per year.

- In cooler regions can do free air cooling where draw in cold air from the external environment

- Non-potable water cooling - eg: sea water cooling for Google in Finland. Note that any filtering or treatment required to use this water adds to the carbon footprint of the DC.

- Does usage include consumption and withdrawal?