https://doi.org/10.1016/j.crsus.2025.100518

One of the authors on the paper, Kevin J. Kircher is the creator of the Distributed Energy Resources course that I wrote about a few months ago. He has a nice bluesky thread where he picks out the highlights.

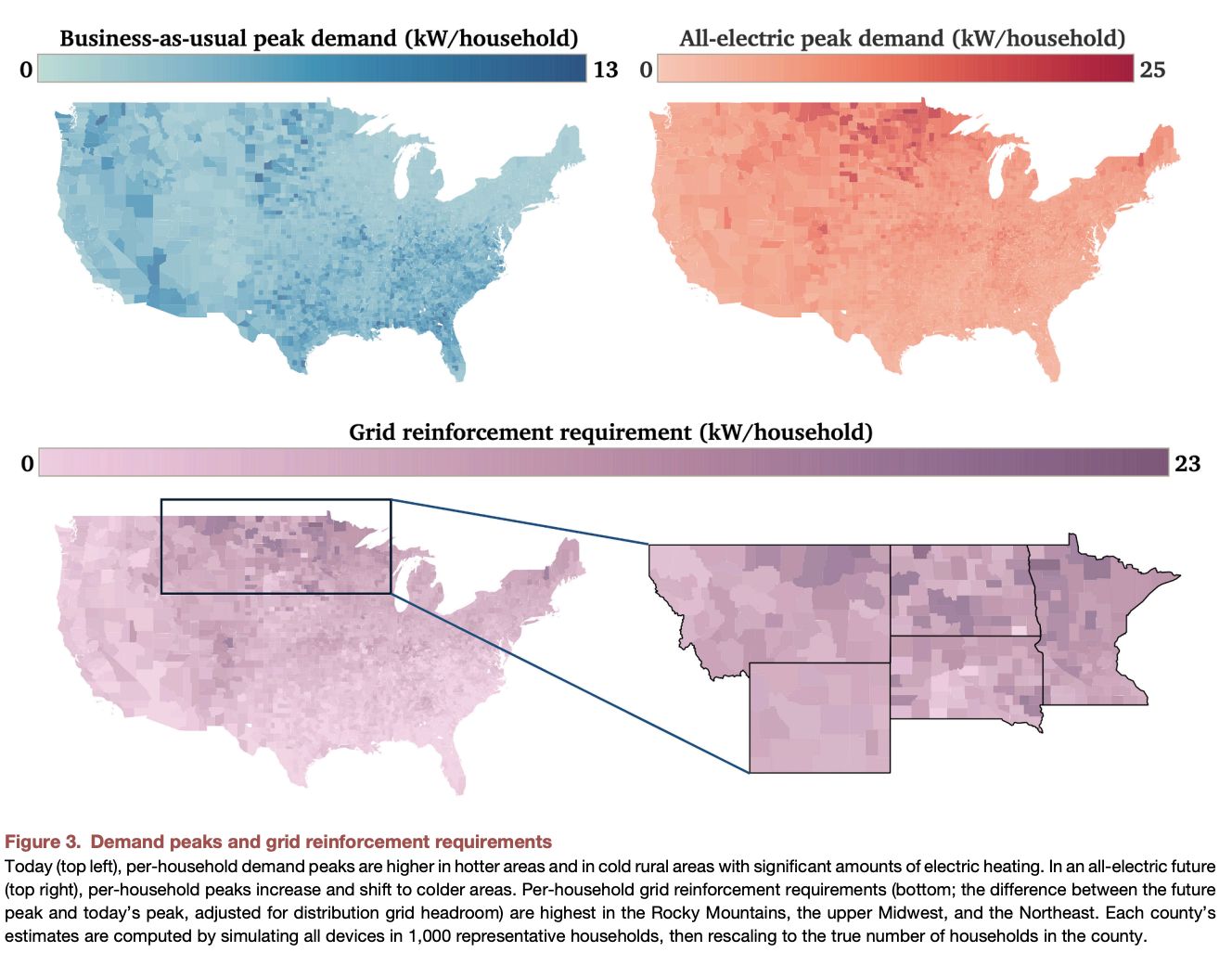

Abstract: Replacing fossil-fueled appliances and vehicles with electric alternatives can reduce greenhouse gas emissions and air pollution in many settings. However, electrification can also raise electricity demand beyond the safe limits of electrical infrastructure. This can increase the risk of blackouts or may require grid reinforcement that is often slow and expensive. Here, we estimate the physical and economic impacts on distribution grids of electrifying all housing and personal vehicles in each county of the lower 48 states of the United States. We find that space heating is the main driver of grid impacts, with the coldest regions seeing demand peaks up to five times higher than today’s peaks. Accommodating electrification of all housing and personal vehicles is estimated to require 600 GW of distribution grid reinforcement nationally, at a cost of 790 billion, or 6,400 per household (95% confidence intervals). However, demand-side management could eliminate over two-thirds of grid reinforcement costs.

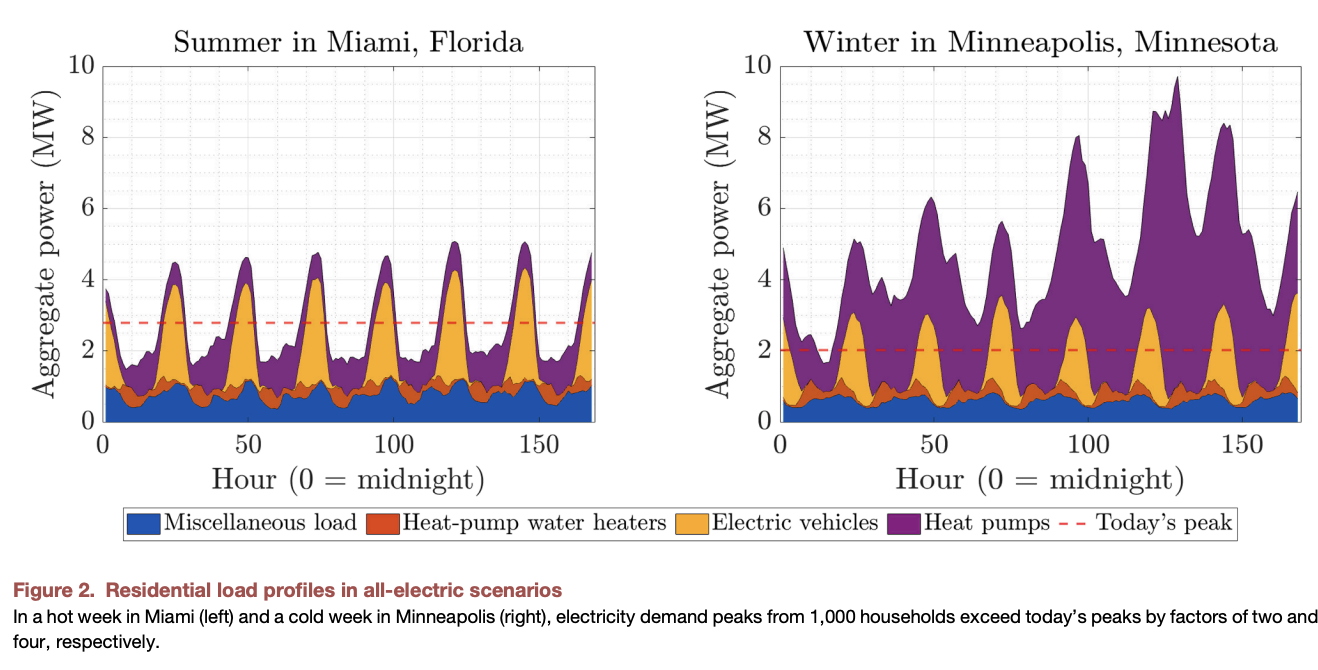

I liked the detailed demand breakdown for 100% electrification of houses and vehicles in the US. Unsurprisingly, EVs are a big chunk, but I hadn’t realised that heating is going to be the biggest driver in many locations both because these places get very cold in the winter, and because heatpumps get less efficient as the temperature differential between heat source and destination goes up. This leads to big differences in increased peak demand across the country with Miama seeing a 2x peak demand increase while Minneapolis sees a 5x increase!

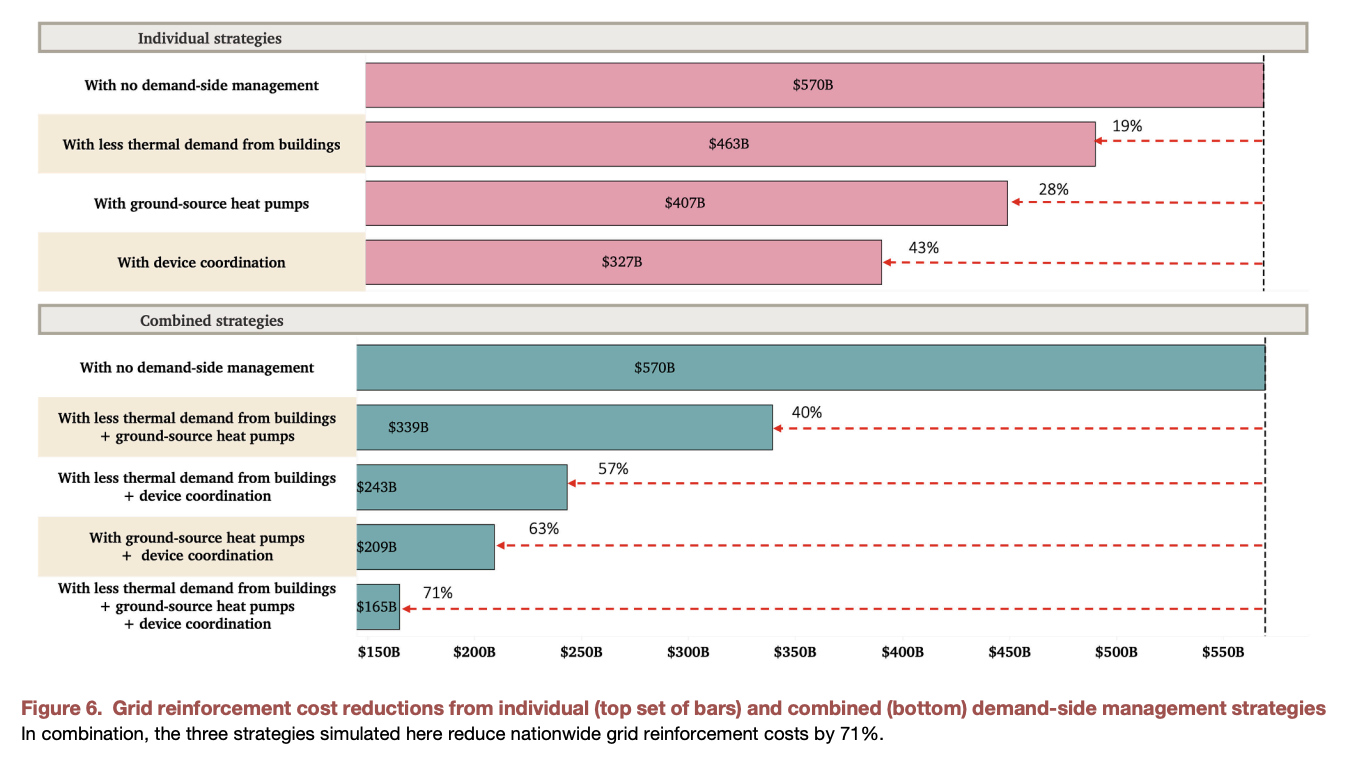

This increased peak load requires lots of money for more grid build-out and maintenance, and the rest of the paper looks at three mitigations:

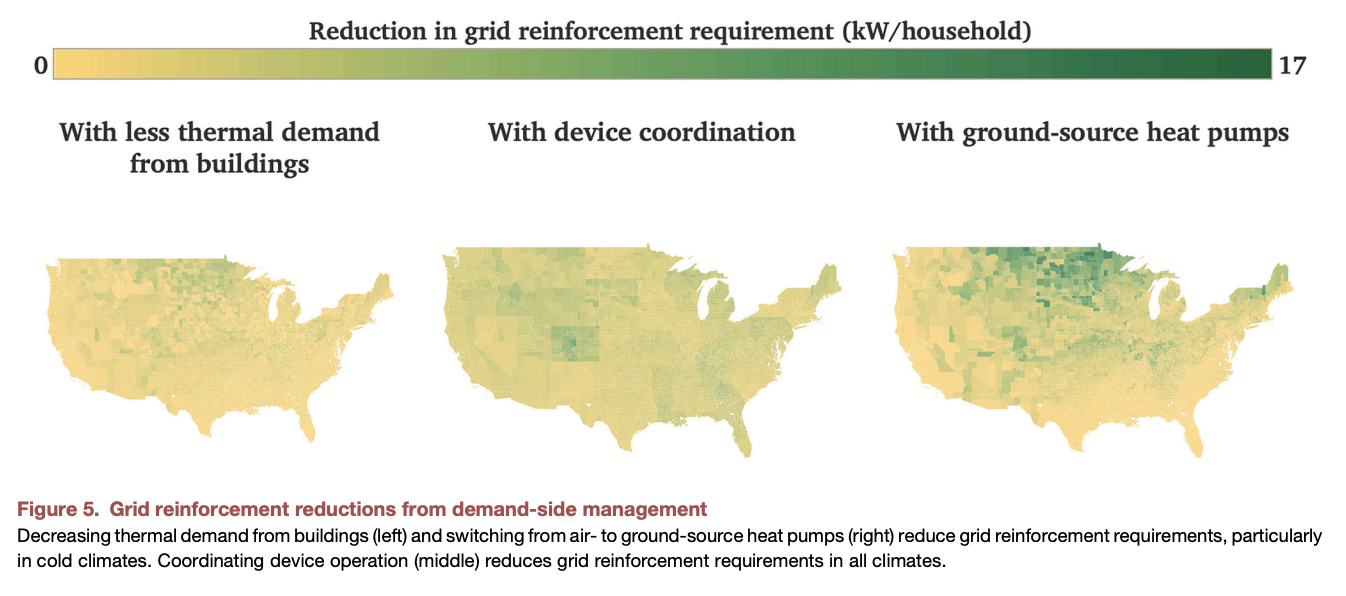

- Reducing thermal demand from buildings by improving insulation and air sealing.

- Demand coordination via smart devices.

- Switching from air sourced heatpumps to ground sourced for a ~30% efficiency improvement.

The news is good. Demand coordination on its own could drop costs by 43%. This is particularly exciting because it requires very little extra investment compared to the other two options, assuming the 100% electrified future has sufficient device automation to make this just a software problem.

And combining all three mitigations could chop off up to 70% of the cost.

But this isn’t a single-party savings calculation. We’re talking about savings to utilities that are unlocked by increased costs to the consumer (improved home insulation or changing heat pump types) or consumers giving up some control of their energy usage. So some of those consumer costs will need to be subsidised.

Notes

- Looking at demand side-management as an aid to increased load on the distribution grid (medium voltage), not transmission.

- “On average over the three coldest climate zones (zones 5, 6, and 7), future peak demand is likely to be three times higher than today’s peak.”

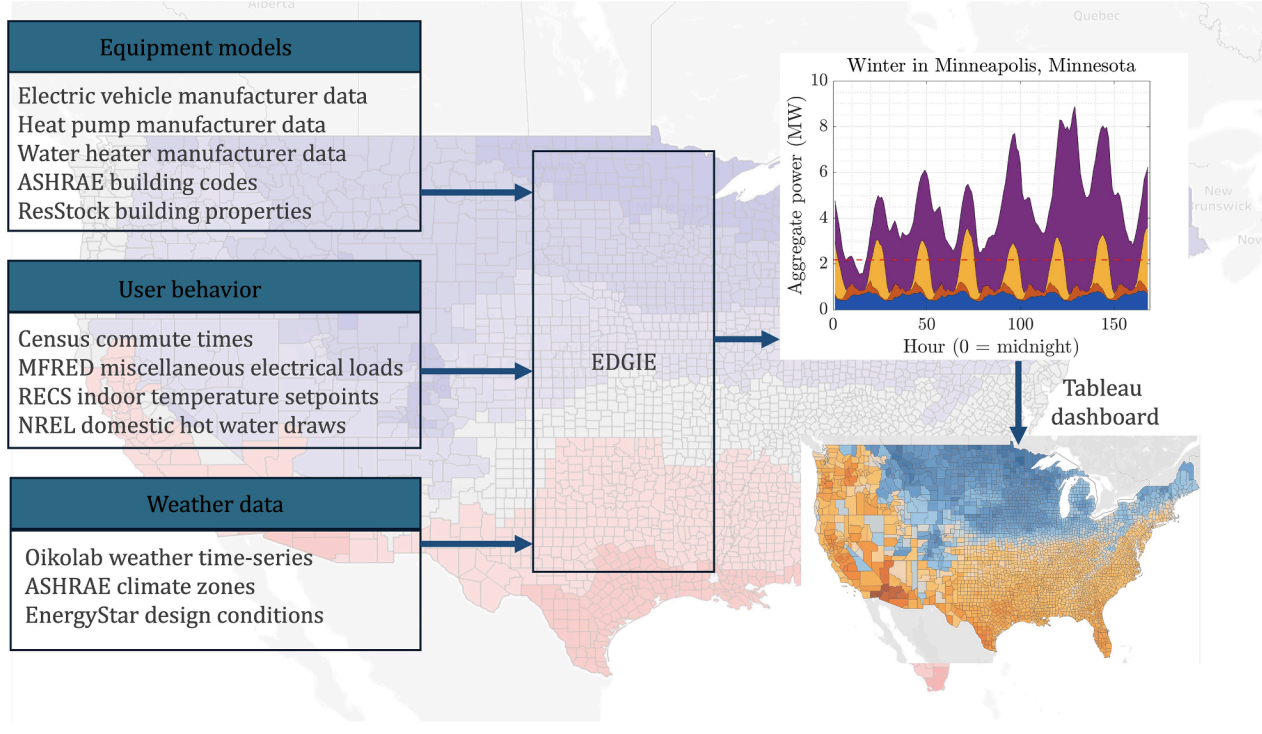

- open-source EDGIE (Emulating the Distribution Grid Impacts of Electrification) toolbox.

- Simulated two scenarios: business as usual with existing housing and transport stock etc, and 100% electrification.

- So 2x electricity increase in Miami mostly due to EVs, but 5x in Minneapolis mostly due to heat pumps. Heat pumps also become less efficient as ambient temperature goes down. This is why ground-source heat pumps use 30% less electricity in simulations.

- Peaks in business as usual tend to be in areas that require more cooling, whereas it’s for heating in the 100% scenario.

- Many southern areas with mild winters require little or no grid reinforcement

- Big variation in grid reinforcement requirements between adjacent counties can be explained by differences in housing types and sizes, levels of insulation and air sealing, driving patterns, weather extremes, or other location-specific data.

- Grid reinforcement cost estimates account for both the capital costs and in the increased maintenance costs for a larger grid.

- How can demand-side management help?

- ground-source heat pumps use about one-third less electricity than air-source per unit of heat output